I like to look back before I leap forward – although no one could be blamed for sprinting away from the talons of 2020. But, as this year comes to a close, I’ve tried to find a way to organize a tangle of asynchronous reflections.

I knew the process wouldn’t be neat, nor would my conclusion have a bow. Still, I searched for the essence of this unforgettable swath of time; A way to put the file …not so much away, but in the cabinet. Maybe you have, too.

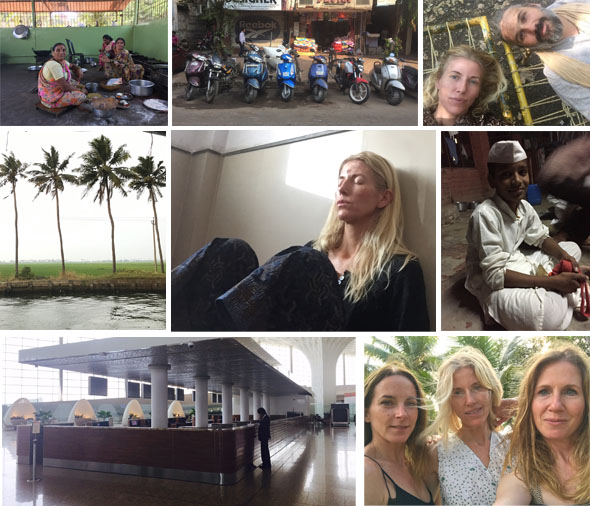

What I found is that in a year like no other, opposing sets of circumstances always seemed to be uncannily, at times disturbingly, within arms-reach – even minutes reach – of each other. And while we were united by shared assaults against life as we knew it, our individual experiences within the bounds of these calamities varied so widely.

In some lives, things were “unprecedented,” changing daily and generally stressful. But they were survivable. Parents toggled between repetitive meal prep, academics they’d long forgotten and attempts at meaningful work. Families had little privacy, relentless proximity. Sinks were full of dishes, and strangely both uncertainty – and predictability – were a constant.

In others, disease, outrage and mother nature devastated towns and families. Politics tore through others. Homes and incomes disappeared. Businesses evaporated. And, in too many cases, loved ones never came home.

We sought ways to treat our fragility and anxiety.

We weren’t sensitive enough.

We were so sensitive.

Sometimes we were “blessed.”

Sometimes we were everyone else.

And of course, people faced the usual crises and curveballs that had nothing to do with any of this. Because contrast – light and dark, grief and joy – are always neighbors, whether visible or not.

So, it’s not a revelation that we exist in a state of vulnerability, in all our days, mitigated by moments of super-human strength, effective distraction and a false (but convincing) sense of impermeability.

But there was something else: There was good news in 2020, which (for some reason) is very hard to say or even to write.

Amidst all of the wreckage, there was still magic to be found. Miracles, even. As a message-maker, it’s possible that I have a hyper-awareness of the words and subtext of culture and zeitgeist – and maybe a sensitivity to how the copy gets crafted, all things considered (which they always have to be, in my world.)

But…

Celebrating anything almost seemed worse than unsympathetic, it felt hedonistic. There were times in my own life, and still are, where I might normally share some sacred or worthy moment with my small corner of the world, but it has felt trite. I’ve had reluctance to fully enjoy or rejoice, even privately, in the midst of so many who have lost something they couldn’t get back.

Unrelated personal struggles, or even victories, can feel so irrelevant in the context of all else. It has even been hard to mourn legitimate but non-threatening elements to life like serendipity and chance encounters, when lives and livelihoods have been decimated.

Messages across social media urged gratitude – in various ways and at different volumes. This isn’t an unexpected (or disingenuous) reaction – it’s often where we go in the ruins. And I did find thanks easily, and daily.

Yet in 2020, some of those messages of blessedness bordered on sanctimonious, as though some of us were chosen for a lesser nightmare, while others were left to suffer more profoundly. There was a certain packaging that bothered me – a need for something positive to come from a variety of difficult, painful, inexplicable situations.

A few years ago, after the attacks in a Paris nightclub, I published a piece called Dualite, with much the same sentiment. The tragedy in Newtown, CT, had a similar agony. As humans, we must function in our roles and vocations, with our own hopes and dramas, while living in the presence of the irreconcilable. Nothing good, at all, comes of some events.

I’ve struggled to acknowledge and feel all of this; and also wondered where I haven’t acknowledged enough.

Have you experienced this sensation I’m trying to identify?

Is it a cautiousness in vocalizing (or demonstrating?) happiness… because your mind and heart feel a responsibility to shoulder some of the collective weight? For me, it’s a sense that if I fully give in to pleasure, it robs someone, somewhere, of some effort to help carry their more burdensome load. Instead of nourishment, I’ve felt it as a withdrawal.

Metaphysically, this has no basis. Literally it might not either. But it has been my feeling.

I don’t have a tidy answer (not sure there should be, actually.)

But here’s what’s clear.

If we got the gift of nothingness, we were lucky.

If we weren’t in a hurry, we were lucky.

If we didn’t have to show up to active duty in one of the handful of wars waged this year, we were lucky.

If we gained time… with ourselves, with our home-mates, with friends in need of connection, we were lucky.

I asked myself a question at one point, which was: In the face of all that is wrong, unjust, inhumane, unfair, disheartening, dishonest, disproportionate… how can I keep my own life moving forward, doing valuable things, in service, even if those projects aren’t directly tied to survival? I resolved that advancing personal or professional missions has never implied an ignorance or disassociation from the gravest, most urgent of matters in our orbit. As long as action is also taken where it counts.

And.

Anger or sadness can’t be the only legitimate feelings.

Nor is obliviousness an option, as it cheats us of an opportunity to feel the experience of others who aren’t like us.

So, maybe the practice is assimilation, versus compartmentalization; holding the brutal, and the beautiful, without the need to make immediate sense of either. This is always the truth of life, not just these past nine months.

We can find real silver linings, it’s true. I’m not denying that there are some. But I think we often extract them as a public relations tactic – an escape hatch to avoid (said plainly), really hard feelings. It’s natural to want to turn lemons into lemonade – to shove 2020 into the vault and throw away the key. It’s the way we finish the long sentence that was this year.

But we went through something, and we went through it alone and together.

People will come out with scars.

Some will walk, breathe and exist differently for a very long time.

We aren’t going back… to anything. No such thing.

Our work is beginning, not ending.

Instead of renouncing 2020 – or allowing it to be relegated to a meme or idiomatic expression – could we recognize this year without resolving to learn a lesson? Could we walk with our experiences and not away from them?

It can’t become the year that wasn’t.

It was so much.

Here’s to everything, in 2021.